It’s been a while since I wrote about posters. Right now I’m working on an update of the MDRES book and so I had to deal with the topic again. The following text deals with the presentation of posters.

The last three posts about posters have been about designing posters, in response to Mike Mirrison’s #betterposters initiative. In the first post, I suggested a poster template with a dark background, which was criticized for wasting a lot of ink. Therefore, I offered a light version in the second post. When I learned that many people do not use vector graphics software to design the posters, but a software for presentations such as Microsoft Powerpoint, Apple Keynote or LibreOffice Impress, I also offered templates for these programs in a third post.

Posters are presented in large foyers or halls, often together with large numbers of other posters, organized according to themes that usually relate to oral sessions presented on the same day. The participants in the oral sessions, including the conveners, the presenters, and the audience, can visit the posters, meet the authors, and discuss with them their results. The conference organizers often offer free wine and soft drinks, making the poster sessions an attractive opportunity to meet other scientists and discuss the overall topic of the poster session. These poster sessions are also important recruiting events and provide many opportunities for young researchers, for example for doctoral students seeking postdoctoral positions for after the completion of their theses. Since the time slots available for oral presentations at large conferences are often very limited, most abstracts submitted with a preference for oral presentations actually end up as posters instead.

The models used to organize a poster session can vary from conference to conference, and even within a single conference, depending on the convener. Some conveners allow poster presenters to give a one-minute presentation of their work before the relevant oral sessions, possibly even including the presentation of a single slide. Others organize guided tours through the poster session, usually consisting of a small group of interested scientists going from poster to poster, with the presenters giving a short oral summary of their work and taking questions from the group. In most cases, however, the conference participants wander around individually and discuss the science with the authors at their posters.

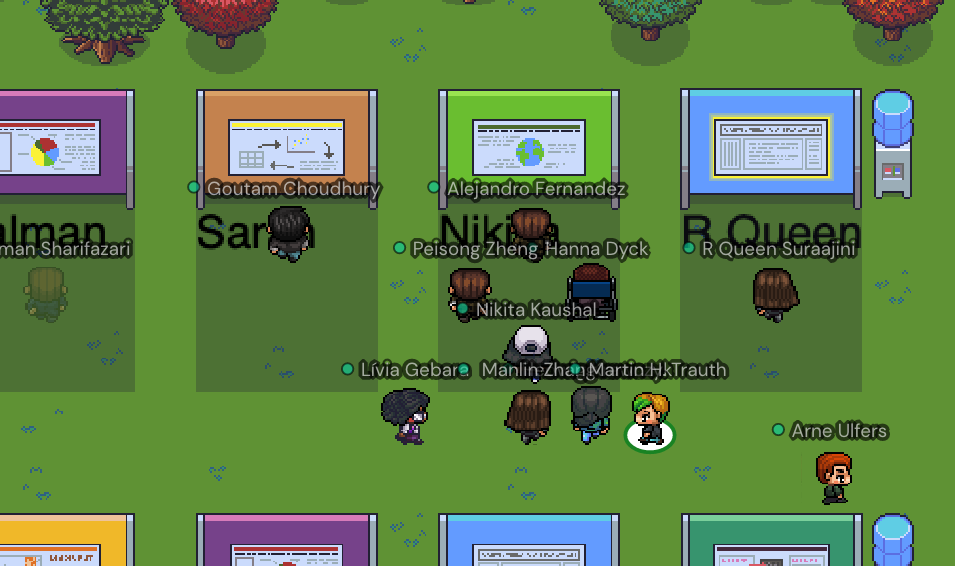

A modern variant of this format is the Presenting Interactive COntent (PICO) Session of the European Geosciences Union (https://www.egu.eu) General Assemblies. Here, short presentations are given in specially set up PICO spots or via Zoom (https://www.zoom.com) at the conference, where interactive posters are shown on a screen on site and in Gather.Town (https://gather.town). Gather.Town is a virtual workspace for workshops and conferences where people can meet and exchange ideas as avatars in a specially designed virtual environment (e.g. a conference building, a café or a garden). Authors have the option of uploading a pre-recorded lecture instead of a live presentation. In addition to the interactive poster, further materials can also be uploaded so that participants can view the content asynchronously.

The trend towards presenting digital posters on screens instead of printing them on a poster board opens up new possibilities for incorporating multimedia and interactive elements. At the PICO sessions, participants have the opportunity to explore a topic further after the short presentation. However, instead of posters, presentations on monitors are used, as is common in oral presentations. The next step, however, is to make the entire poster interactive. An award-winning example is the interactive posters from Future Ocean (https://futureocean.org) at GEOMAR (https://www.geomar.de/), which were realized by the Science Communication Lab (https://scicom-lab.com).

How should one prepare for a poster presentation? Of course presenting a poster to an interested individual or a small group of people is a much less challenging task than giving a talk in a large lecture hall, but nevertheless an inexperienced presenter should write down a few essential facts and conclusions from the poster and prepare a quick summary for presentation when an interested visitor shows up at the poster. A very popular idea is to offer small printouts of the poster (e.g., using A4 format) that people can take home or, if available, reprints of a published journal article that contains the results shown on the poster or related work by the presenter. Some people also like to offer their business cards at their poster boards, QR codes that link to their website, or even their CVs if they are looking for a job. Laptops or tablets are sometimes placed next to the poster board to display material such as movies, computer animations, project webpages, or software tools.

During the actual poster session, which will typically last one or two hours, the authors of the posters are expected to remain at their poster boards, making it difficult for them to visit other posters in the same session. If there are two or more authors presenting the poster they can obviously take turns at the poster board. If only one author is present, he/she can put a note on the poster informing visitors when they will be available to answer questions.

References

Trauth, M.H., Sillmann, E. (2018) Collecting, Processing and Presenting Geoscientific Information, MATLAB® and Design Recipes for Earth Sciences – Second Edition. Springer International Publishing, 274 p., ISBN 978-3-662-56202-4. (MDRES)