AI changed everything, also the way we search for literature, create figures, and write summaries. Teaching a course on collecting, processing and presenting geoscientific information and having published two editions of a book on the topic, it was time for a change. And two new books.

In 2007, I took over a literature seminar from an older colleague. Until then, our university’s seminars had followed a consistent format, similar to those during my own studies in the 1980s. On the first day in mid-October, students were assigned topics such as the San Andreas Fault or the Himalayas. Typically, they were provided with one or perhaps several papers as a starting point. Weeks passed without any progress, as students diligently read the literature and prepared their presentations. Finally, in December, two or three 20-minute presentations were given. Each presentation was followed by a few questions, brief feedback on the quality of the presentation, and then the next presentation commenced.

Initially, I aimed to bridge the significant gap between topic assignment and the first presentations. I decided to reduce this gap to 3–4 weeks, as I believed that this timeframe was sufficient for students to prepare a 20-minute presentation. Subsequently, I expanded the requirements by asking students to prepare a handout in addition to their presentations. This one-page handout included the presentation title and date, the presenter’s name, a concise 200-300 word summary, and a bibliography. This initiative marked the beginning of teaching academic writing, as the handout was subject to comments and feedback.

Next, we delved into the art of preparing a scientific presentation, breaking it down into two key sections: content and technical aspects. To aid in this process, a handout was provided, outlining ten crucial points for planning, designing, and delivering an effective presentation. Although I had limited teaching experience in these areas, I drew upon my extensive personal experience of approximately 15 years in scientific writing and presenting. My colleagues shared this expertise, which is why I invited three of them to share their final conference presentations, each lasting around 12 to 15 minutes, as valuable examples on the final day of the time gap. Additionally, I encouraged participants to actively attend the institute colloquium, where colleagues from both within and outside the institute present approximately 45-minute research talks, a customary practice worldwide.

In 2010, this course format was transformed into a mandatory component of the newly established bachelor’s program in geosciences. Consequently, I discontinued the assignment of papers and instead provided topics, primarily drawn from my own research. The course comprised approximately 65 participants, who were divided into five distinct groups, each assigned a unique topic, such as the relationship between Homo neanderthalensis and H. sapiens. Every two weeks, these groups were tasked with completing a specific assignment and presenting their findings. For instance, they were required to identify the five most significant papers related to their topic or pinpoint the most important hypotheses and controversies within the subject matter. Subsequently, they engaged in graphic design, wrote concise summaries, and drafted a comprehensive conference program. The final exam, which included approximately 65 participants, consisted of individual 200-word summaries, a poster, and a 2-minute presentation on a subtopic of their assigned group topic.

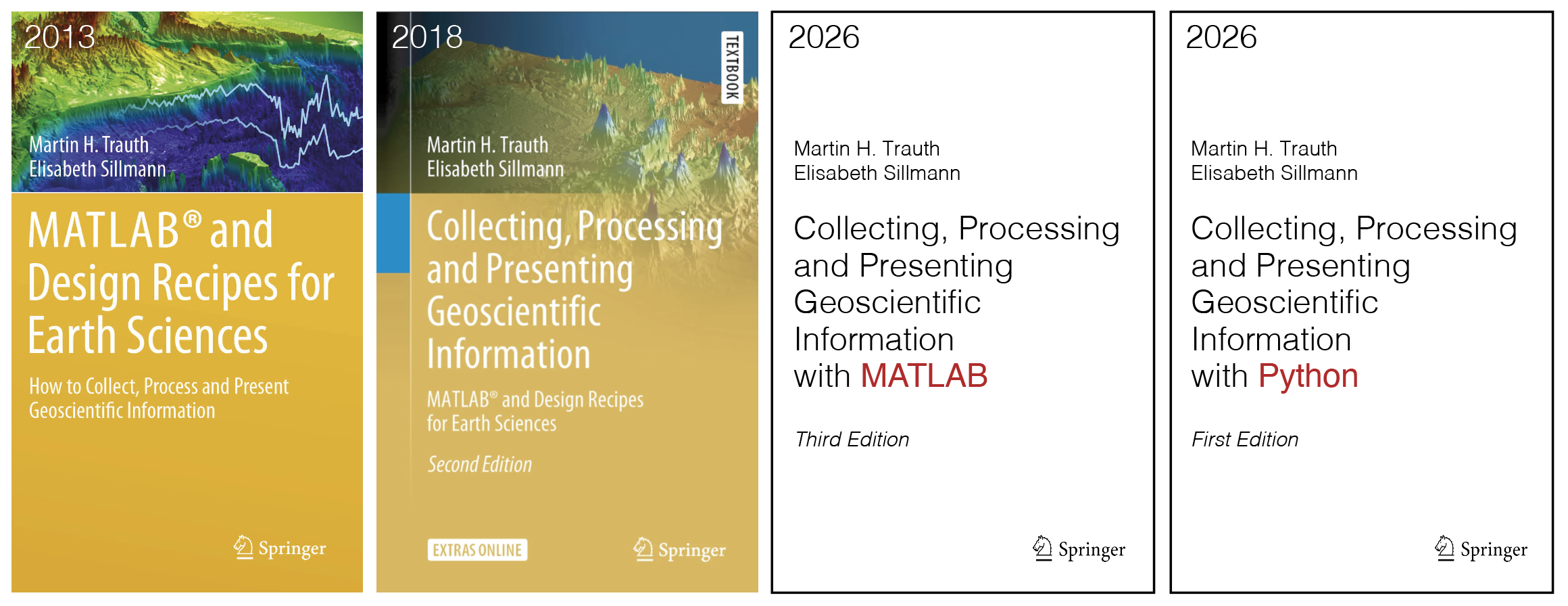

The course was a resounding success, particularly the open course format that largely lacked fixed guidelines on completing weekly assignments and presenting solutions. Consequently, in 2013, I published my second book with Springer titled MATLAB and Design Recipes for Earth Sciences: How to Collect, Process, and Present Geoscientific Information. This book was co-authored with designer Elisabeth Sillmann at blaetterwald-Design. Elisabeth had previously designed MATLAB Recipes for Earth Sciences and other books for Springer. The second edition, with a slightly modified title, was published in 2018 with Springer. In the meantime, I taught an advanced course on the subject for students in the Master’s program in Geosciences.

In November 2022, the introduction of ChatGPT revolutionized the course. Today, AI is used entirely or partially for tasks such as literature and data search, creating graphics, posters, and presentations, and formulating summaries. While many colleagues consulted our lawyers to determine how to prohibit AI use in their task sheets, I embarked on an experiment with AI. After a brief introduction to the principles of artificial neural networks, we consistently utilized AI to save time and enjoy the amusing AI errors.

The students appreciated the autonomy to decide whether and to what extent they used AI. The exams also underwent changes. While short essays, posters, and short presentations remain the foundation of performance assessment, students now submit a fourth part of their work: a declaration of independence. Similar to a lab report, this declaration documents the use of AI. Although the form is not specified, the initial examples are well-crafted and will be evaluated.

It became evident that the second edition of the book was also outdated, so Elisabeth and I resumed our work. The new book has undergone a complete rewrite, retaining only a small portion of text from the previous editions. Notably, as with the recipe books, there will also be MATLAB and Python versions. We have eliminated lengthy technical descriptions, which were present in previous editions and quickly became obsolete after software updates. Instead, concepts are explained, followed by and separated from examples, which can be easily updated in the blog you are currently reading. Naturally, there is once again a comprehensive electronic supplement. The book’s design follows that of the Signal & Noise book, which also includes a brief introduction to the concepts, followed by examples.

The books are currently with my editor, Ryan DeLaney, and will be submitted to the publisher in a few weeks. Ryan should now have a little less work to do with the texts, as I have proofread them—as well as this blog post—with the help of AI, namely Apple Intelligence! I anticipate that the books will be published in mid-2026. I hope you enjoy the new books as much as you appreciate my other books!

Contents

1 Scientific Information in the Earth Sciences

2 Introduction to Python / MATLAB

3 Searching for and Reviewing the Scientific Literature

4 Searching for and Processing Scientific Data

5 Visualizing 0D and 1D Data in the Earth Sciences

6 Visualizing 2D and 3D Data in the Earth Sciences

7 Image Processing in the Earth Sciences

8 Editing Graphics, Text, and Tables

9 Scientific Writing

10 Creating Scientific Posters

11 Creating Oral Presentations

12 Building a Scientific Career

References

Trauth, M.H., Sillmann, E. (2026) Collecting, Processing and Presenting Geoscientific Information with Python – First Edition. Springer International Publishing, in press.

Trauth, M.H., Sillmann, E. (2026) Collecting, Processing and Presenting Geoscientific Information with MATLAB® – Third Edition. Springer International Publishing, in press.